As a record collector, I’m not really a completist. I generally don’t have the urge to collect all the albums by a single artist, or all the albums on a particular label, or the like. There are a couple of exceptions. At this moment I have collected about half of all of the early electronic and computer music that Nonesuch Records put out in the late 1960s and early 1970s. Why have I decided to pick this as one of my “completist” record collecting goals? First and foremost, because the music is totally compelling, experimental, and bonkers—some of it tests the limits of just how bonkers my taste goes. Some of it is so experimental that I don’t even think it works, which is fascinating on its own. Second, for the most part they are relatively affordable and not super difficult to find. Third, most of them have a uniform design which I find compelling; they (mostly) match together as a set.

This is the first part in what I imagine will be a series of blog posts about the various computer and electronic albums from Nonesuch that I currently have or may obtain in the near future. I was surprised that Nonesuch does not have an official series for these albums as they do for their Explorer Series and International Series albums. Most of this shock is due to the fact that Nonesuch commissioned many of the works on these albums, so I assumed that Nonesuch would have officially grouped them together. But alas, they do not. Thank goodness for Discogs, which I used to find the electronic albums I either didn’t already own or didn’t already know about. It’s possible I might have some holes in my list. Could I finish my collection in one evening by moving my Discogs wishlist right into my Discogs cart? Yes I could, but what fun is that? With the exception of the album I’m about to discuss, I’ve found all of my Morton Subotnik, Donald Erb, Iannis Xenakis, Charles Dodge, and other LPs out in the wild, as it was meant to be. And I will do my best to buy the remaining holes in my collection (about 7-8) the old fashioned way, but I might have to resort to Discogs or eBay in a pinch.

But without further stalling, here’s Part 1:

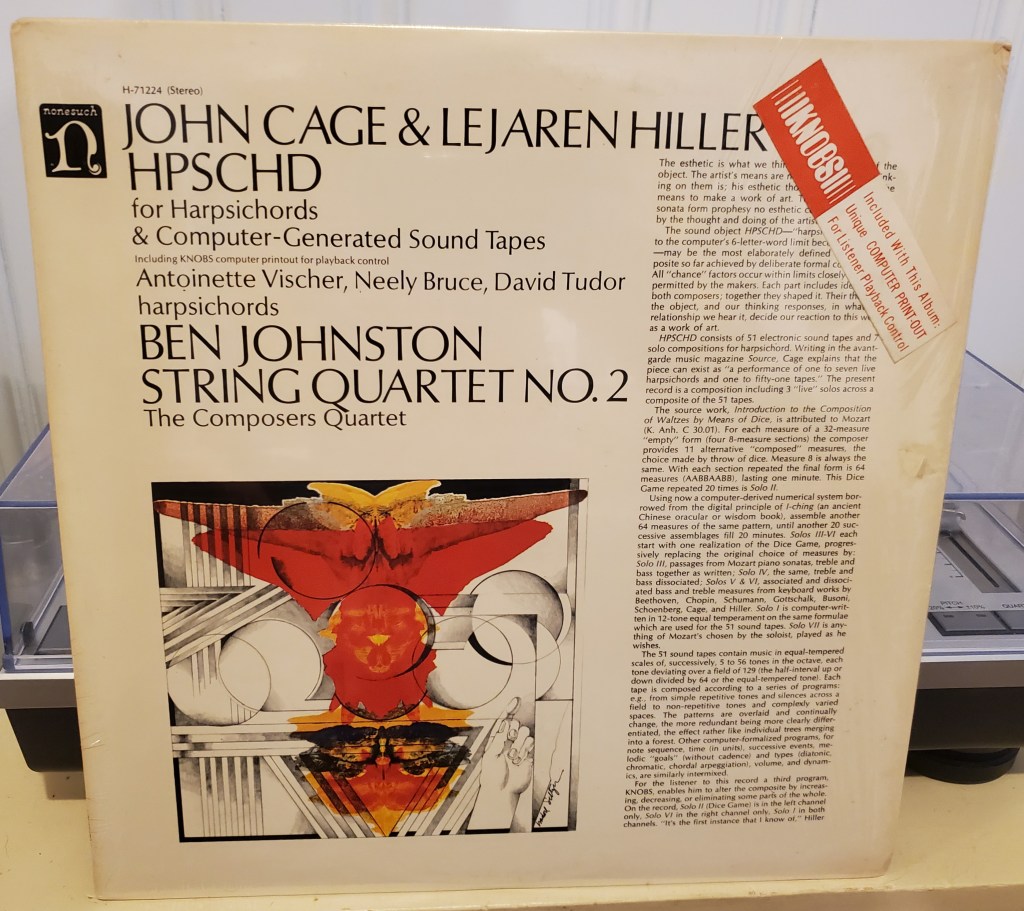

One of my most recent acquisitions is HPSCHD/String Quartet No. 2, released on Nonesuch Records in 1971. The first side consists of the piece, “HPSCHD,” composed between 1967 and 1969 by John Cage and Lejaren Hiller, which is written “For Harpsichords and Computer-Generated Sound Tapes.” The music is as crazy as one can imagine: think aristocratic genteel seventeenth-century salon recital being mangled by a pack of glitched-out Atari consoles gone feral. “HPSCHD” is pure experimental postmodern pastiche if there ever was such a thing. Side two contains Ben Johnston’s “String Quartet No. 2,” written in 1964. Although Johnston’s string quartet is one of my favorite works in that genre, I primarily bought the album for “HPSCHD.”

The album, which is part of the permanent collection of the Museum of Modern Art and featured in the 2018 exhibit “Thinking Machines: Art and Design in the Computer Age, 1959–1989,” had been in my Discogs wishlist for quite some time.[1] I purchased this album for two reasons: first, the music is unlike anything I have ever heard before; and second, it was a hole in my Nonesuch collection. I bought this specific copy for one all-important reason: it was sealed.

I don’t usually care if the old records I buy are sealed. I mean if I come across one it’s nice because they are new records. In this case, however, I deliberately waited until a sealed one came up for sale on Discogs. There are some collectors who attempt to buy a sealed copy of every album they already own as a backup copy. That’s not me. Getting a sealed copy of this record was the only way I knew that, barring any mishap at the pressing plant, the record would come with the original insert in perfect condition. I could have bought unsealed copies that the dealer claimed included the insert, but I didn’t want to count on the dealer’s description and trust what kind of condition it would be in, so sealed it was.

What makes the insert to “HPSCHD” special is that it’s more than just generic liner notes or a photograph or a poster or the usual kinds of things that might come with a record. In this case, it’s a wholly unique computer print-out, one of a set of ten thousand, that provide the listener with instructions on how to control the playback of the piece. Essentially, in very John Cage-ian fashion, the insert allows the listener to become a performer. In theory, this meant that there could be 10,000 unique performances of “HPSCHD,” although now that figure must be much less, as surely a great number of the inserts have been lost to time.

Before buying the album I knew that it came with an insert with some kind of instructions or code or punch cards that was used to alter the album’s playback, but I didn’t know the specifics and didn’t really understand the descriptions I read online. All I could tell is that it has do something with a computer program or something called KNOBS. Did I need to have the same sort of computer Cage had in the late 60s in order to achieve the intended result? I surely hoped not.

Now, let’s pause for a second. When the album arrived and I opened the box, the realization fully struck me: this is a brand-new record. It is over fifty years old, but still brand new. If I had seen it in the “new vinyl” section of the record store and didn’t know anything about it, I might have assumed it was a brand-new reissue of a previously released album that was fresh from the pressing plant. Which made me question my intentions. Should I even open this? It’s 51 years old, but new. I felt a pang of guilt at the very idea of opening it. It felt like I would be violating it somehow, or breaking some sort of rule against nature. This album was a survivor. Maybe it should keep surviving and I should just buy a copy that wasn’t unspoiled.

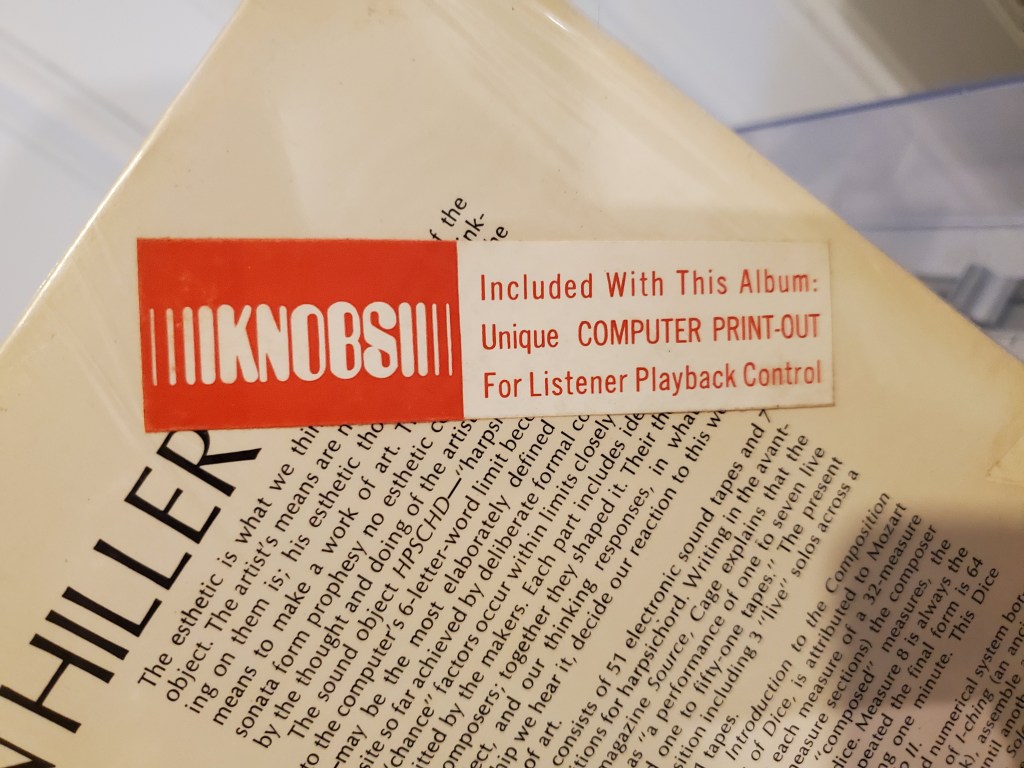

After letting it sit for a couple of days, I remembered that buying records just to have them sitting unplayed on a shelf is antithetical to my practice as a record collector. So I took a deep breath, held it in, swallowed every urge to keep this record in new condition, and slid my fingernail into the shrink and opened it up. I immediately stuck my nose into the sleeve and breathed in. This was 51-year-old air—of course I was going to sample some of that. It smelled like cigarettes—as if it came from my grandma’s collection. Luckily the cardboard sleeve itself did not smell like cigarettes, only the air. Usually when I open a new record I pull the shrink wrap off because I generally dislike the feeling of shrink wrap against my fingers. And if I buy an old record still in the shrink, I pull it off even faster, because it feels extra brittle or sticky or gritty or staticky—whatever it feels like, it’s not nice to hold in the hands. In this case, I left the shrink alone, as it had a sticker that read: “KNOBS: Included With This album Unique COMPUTER PRINT-OUT For Listener Playback Control.” I wasn’t about to lose the sticker by removing the shrink wrap.

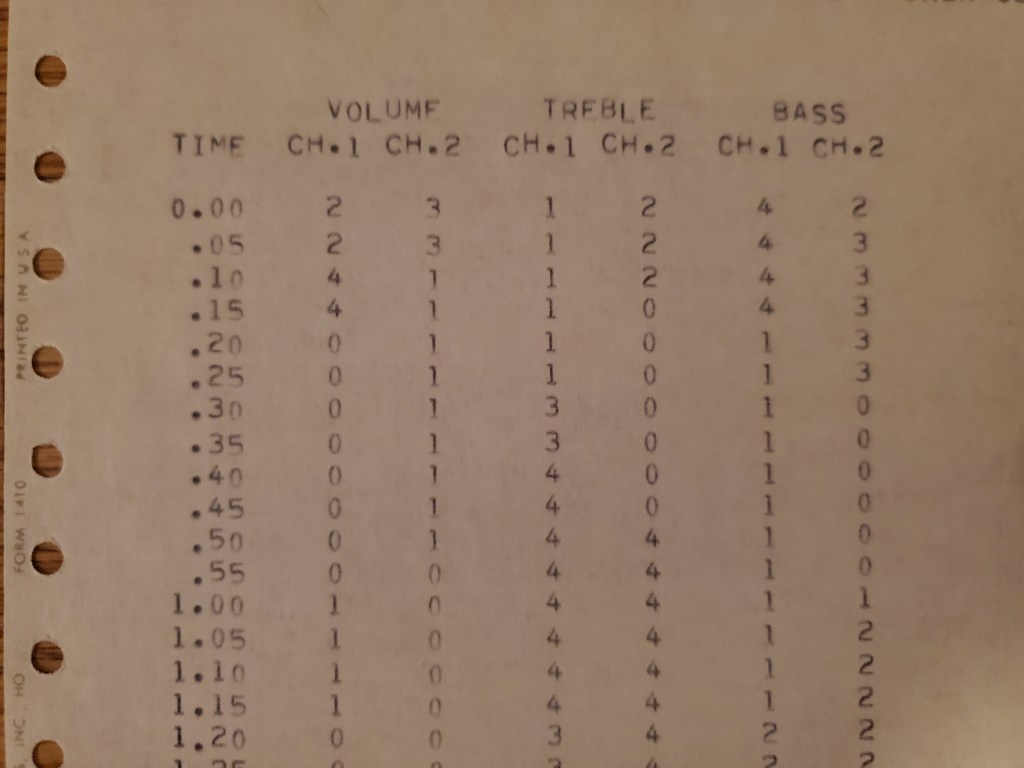

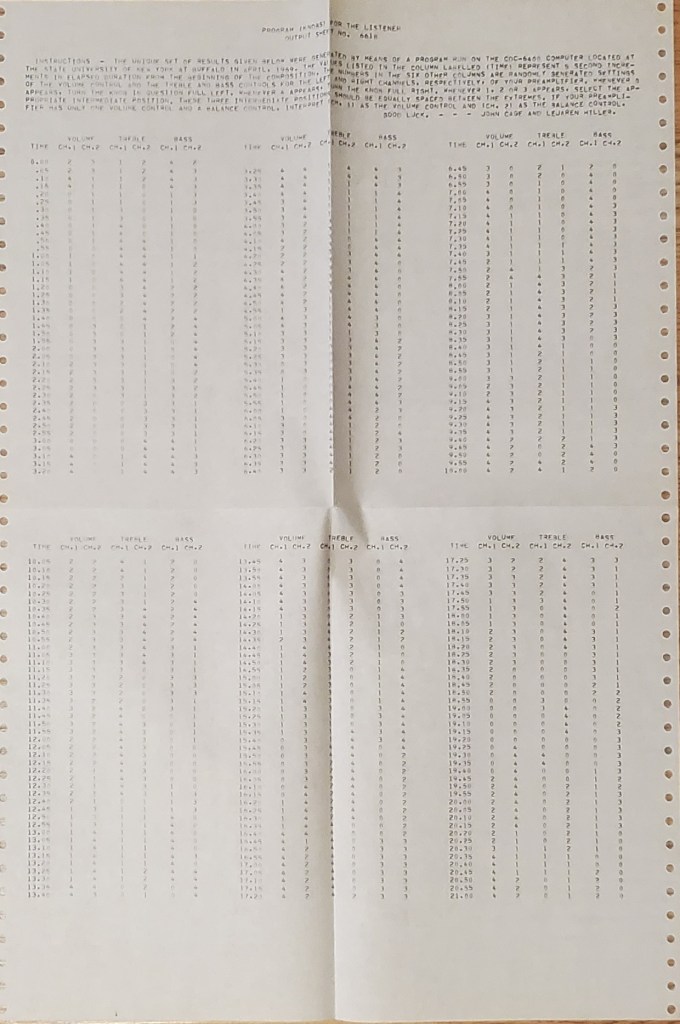

Usually my first move would be to listen to the record rather than to check to see if it came with any inserts, etc. Not this time. I went right for the insert, which was a large sheet printed from a dot matrix printer that was folded into quarters. (A later CD reissue came with a set of fifteen cards rather than a poster sized sheet of paper.) I’m not sure why the dot matrix paper surprised and pleased me; I’m old enough to have printed many things from a dot matrix printer and then satisfyingly tore the edges off. I was afraid that the instructions would make my chance to influence the playback of the music impossible or that they would be incomprehensible to anyone without a computer science or engineering degree. Luckily, this was not the case. The insert reads:

PROGRAM (KNOBS) FOR THE LISTENER

OUTPUT SHEET NO. 6618

INSTRUCTIONS – THE UNIQUE SET OF RESULTS GIVEN BELOW WERE GENERATED BY MEANS OF A PROGRAM RUN ON THE CDC-6400 COMPUTER LOCATED AT THE STATE UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK AT BUFFALO IN APRIL, 1969. THE VALUES LISTED IN THE COLUMN LABELLED (TIME) REPRESENT 5 SECOND INCREMENTS IN ELAPSED DURATION FROM THE BEGINNING OF THE COMPOSITION. THE NUMBERS IN THE SIX OTHER COLUMNS ARE RANDOMLY GENERATED SETTINGS OF THE VOLUME CONTROL AND THE TREBLE AND BASS CONTROLS FOR THE LEFT AND RIGHT CHNNELS, RESPECTIVELY, OF YOUR PREAMPLIFER. WHENEVER 0 APPEARS, TURN THE KNOB IN QUESTION FULL LEFT. WHENEVER 4 APPEARS, TURN THE KNOB FULL RIGHT. WHENEVER 1, 2 OR 3 APPEARS, SELECT THE APPROPRIATE INTERMEDIATE POSITION. THESE THREE INTERMEDIATE POSITIONS SHOULD BE EQUALLY SPACED BETWEEN THE EXTREMES. IF YOUR PREAMPLIFIER HAS ONLY ONE VOLUME CONTOL AND A BALANCE CONTROL, INTPERPRET (CH. 1) AS THE VOLUME CONTROL AND (CH. 2) AS THE BALANCE CONTROL. GOOD LUCK – – – JOHN CAGE AND LEJAREN HILLER.

That’s much more straightforward than I was expecting. And also, “good luck”—how cool is that? The only difficulty, besides changing the settings on the preamplifier/amplifier every five seconds, is managing to somehow change up to six knobs—left and right for each volume, treble, and bass—at once. Perhaps if I found two friends the three of us and our six hands could manage it. Actually, a time keeping fourth person would be handy to cue every five seconds. I’m sure that fifty-one years later, however, that it wouldn’t take much coding knowledge to create a program that once the data was entered, would automatically make the adjustments to the volume, treble, bass, and balance and “perform” the piece as the printout dictates. And imagine, if I learned how to do that, I could collect any number of copies of this album that still had the insert and make the corresponding number of realizations of the composition. It’s not a horrible idea. I’ve had worse.

The entire process of opening the album, breathing in the old air (perhaps not the smartest decision), unfolding the insert, reading the instructions, and working out how it was to be done was just as, if not more thrilling than when I first heard the music and decided I had to buy the record. It was hard to believe that I had reservations about opening the album. It’s generally not a difficult album to find if one doesn’t mind doing their record shopping online and it’s not prohibitively expensive for most folks. If I had decided to leave this one in its untouched state I could have found another copy, although probably not a sealed one for the relative bargain price I paid of twelve dollars.[2]

The excitement and physically affective experience of going through just the insert alone was enough to reaffirm my conviction that records are meant to be played, handled, and enjoyed, and that my early instincts of leaving this copy sealed were absolutely wrong. I almost feel sorry for collectors who, by buying sealed copies as investments or as trophies to show off or as backup copies of the albums they actually listen to, do not take the full advantage of the pleasure and joy the items in their collection can give them. The experience of discovering HPSCHD and its insert is one of the main reasons why I collect, and for a moment, I almost forgot that.

[1] Item detail page for Various Artists with John Cage, Lejaren Hiller, Ben Johnston HPSCHD/String Quartet No. 2, 1969, Museum of Modern Art https://www.moma.org/collection/works/184320? Accessed May 21, 2023.

[2] The cheapest sealed copies for sale in the United States on Discogs as of the early draft of this essay in May, 2023, started at $50.

Leave a comment